California: 1769-1848

A sequel to California: the first three centuries

When Junípero Serra blessed the ground at San Diego, he stood on a coastline glimpsed only by Manila galleons in living memory. The Spanish knew almost nothing of the hundreds of autonomous peoples whose territories they proposed to occupy. By 1850, California would be part of the United States. Within the span of one human lifetime, a chain of Franciscan missions rose and fell, the province's "nationality" changed twice, its Indian population was shattered, and its future was about to be transformed by flakes of gold in a millrace. This is the story of California as a remote colonial backwater sustained by forced labour and populated by fewer than four thousand settlers, before the gold rush made it the destination of a global migration.

Part 1: The Mission Period / Spanish California

Serra walked thousands of miles to establish the Alta California missions, the ageing Franciscan travelling on foot, often in agony, to plant Spanish civilisation along the Pacific coast. But he was building on contested ground. Spanish California had two parallel authorities that coexisted uneasily: the civil governors appointed by the Viceroy in Mexico, and the mission padres answering to their religious superiors. The law prescribed that governors would supervise the missions and eventually secularise them, transforming neophytes into citizens. The Franciscans, ruling their missions like feudal lords, had other ideas.

The reception from California's native peoples was hostile. Within five weeks of San Diego's founding in 1769, the Kumeyaay tribe launched two assaults on the mission. Just seven months later, when supply ships failed to arrive and starvation threatened, Governor Gaspar de Portolá decided to abandon the mission entirely. Serra pleaded with him to wait. As if in answer to Serra's prayers, on the very day scheduled for departure, the sails of a supply ship appeared on the horizon. The mission survived, but when Portolá departed, he left a young military officer, Pedro Fages, in command. Serra and Fages disagreed on nearly everything, particularly over the pace of expansion.

San Luis Obispo was attacked three times in its first two years, its thatched roof set ablaze by flaming arrows. In 1775, Kumeyaay warriors returned to San Diego, burned its structures, and killed Father Luis Jayme. Still, by 1776, when Juan Bautista de Anza's expedition reached the San Francisco Bay peninsula, new missions were being founded: San Juan Capistrano and San Francisco de Asís that year, Santa Clara de Asís in 1777. The Spanish were not conquering an empire; they were negotiating entry, mission by mission, presidio by presidio, with peoples who owed no allegiance to each other and viewed the newcomers with suspicion.

The bitterest conflict came not from Indians but from within the Spanish hierarchy. Governor Felipe de Neve, who moved the capital from Loreto to Monterey in 1777, was an Enlightenment man who viewed the missions as retrograde institutions. He wanted civilian pueblos established near missions to encourage integration and trade. Serra saw the pueblos as threats. Neve dismissed his objections and founded San José in 1777 and Los Angeles in 1781. He wanted to curtail the padres' authority over neophytes and redistribute mission lands to soldiers and Indians. The two men battled constantly. The governor called Serra "arrogant," "obstinate," and "deceitful." Serra wrote that Neve was "the enemy of the missions" and the reason he could not sleep many nights. Neve blocked the founding of Mission Santa Barbara for years. Serra died in 1784 without seeing it established, leaving behind nine missions stretching along the coast, crude wooden structures with thatched roofs. Neve himself died the same year, just days after Serra. As historian Edwin Beilharz observed, these were "the two men who more than any others had created and shaped California"1, yet they had battled each other to the end.

The underlying conflict was philosophical: King Carlos III and his officials were determined to assert royal authority over the Church. Neve represented enlightened absolutism: the state, not religious orders, should control territory and populations. Serra represented the missionary enterprise: only the Church could save Indian souls, and civil interference threatened that sacred work. Neither side could fully prevail. The missions succeeded because they served Spanish strategic interests, keeping California Spanish whilst Britain and Russia lurked, and because they generated the agricultural surpluses that fed the presidios. The civil government lacked the resources to colonise California without them.

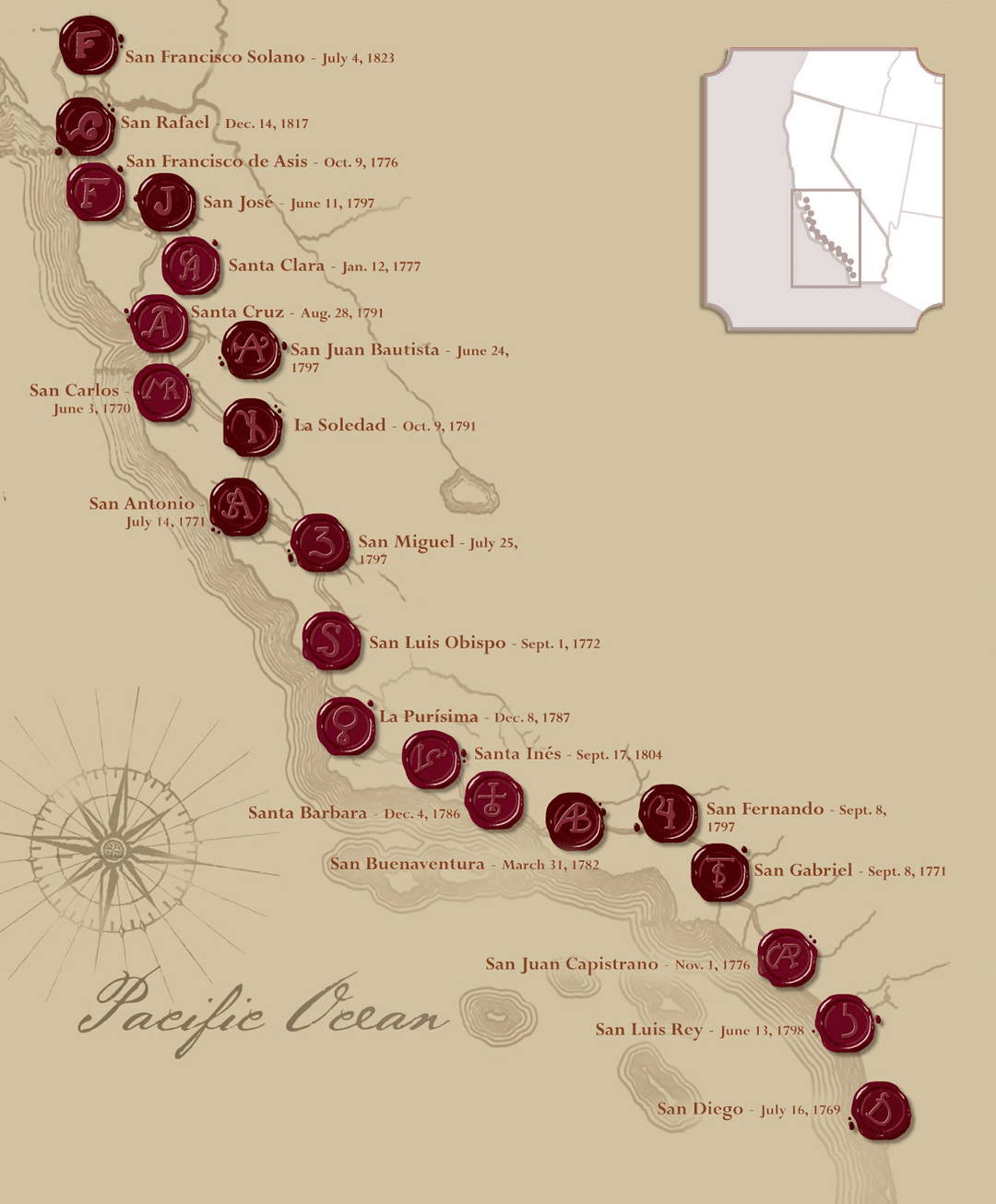

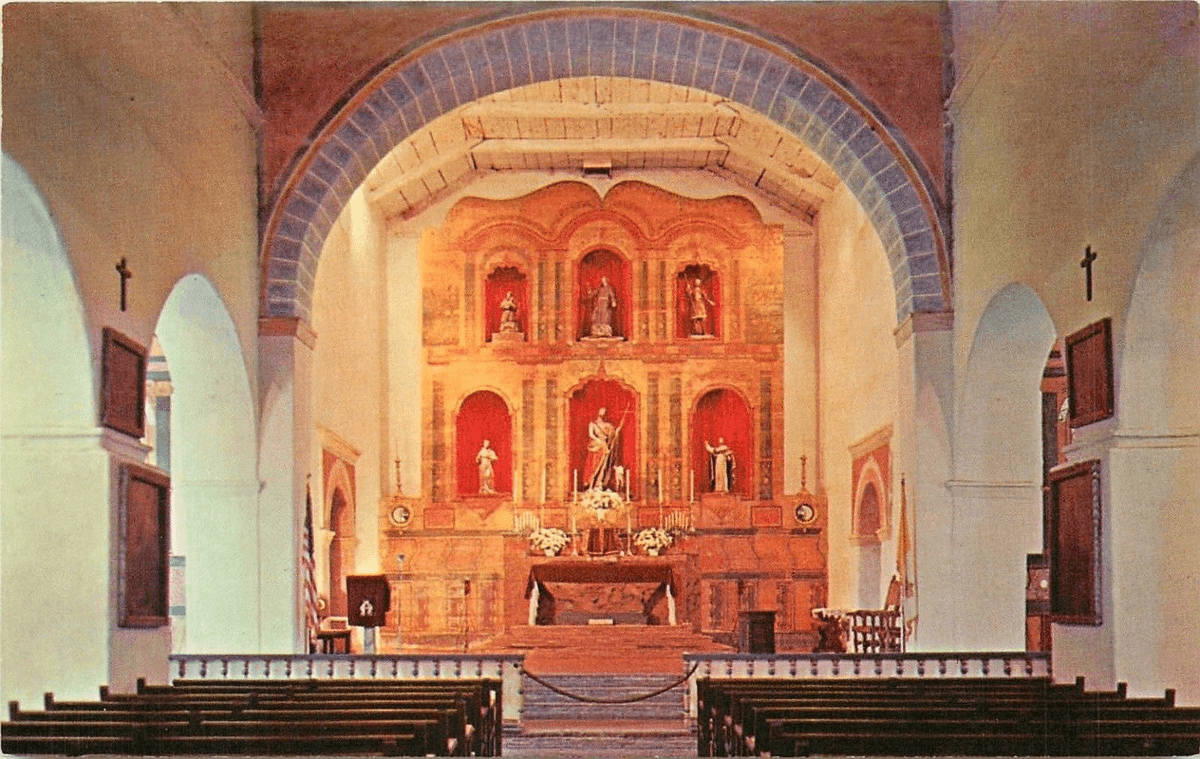

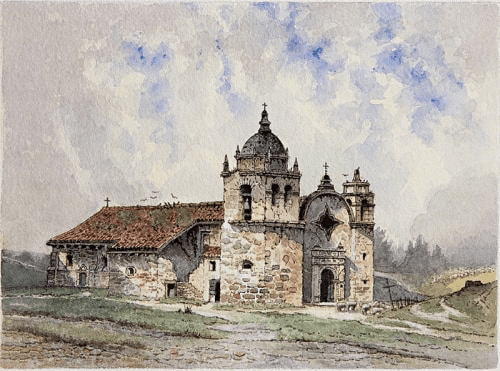

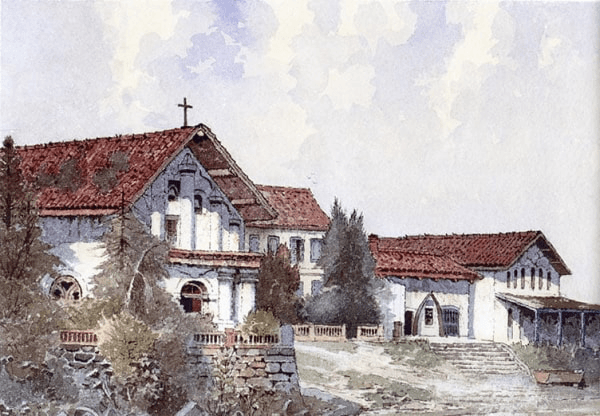

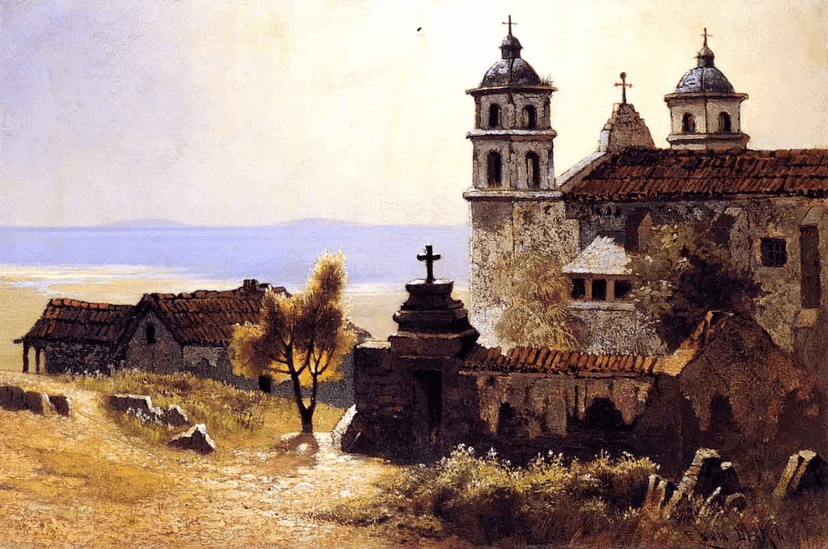

After Neve, Padre Fermín Francisco de Lasuén, Serra's successor, presided over a transformation. Governor Diego de Borica (1794–1800) cooperated with the Franciscans rather than fighting them, arranging for skilled artisans from New Spain to teach trades to mission Indians. The 1790s marked the shift from fragile outposts to permanent institutions. Missions that had begun as crude wood and thatch gave way to substantial adobe and stone. Lasuén founded Santa Barbara in 1786, finally, and La Purísima in 1787. In 1797 alone, four new missions were established: San José, San Juan Bautista, San Miguel, and San Fernando Rey. The great stone church at Mission San Juan Capistrano was dedicated in 1806. That same year, a stone church was completed at San Carlos Borromeo. The mission chain continued its northward march. When Mission San Francisco Solano was founded at Sonoma in 1823, it became the twenty-first and final link in a chain stretching nearly 600 miles, connected by the path that would become El Camino Real.

Spanish law envisioned missions as temporary institutions lasting ten years, after which Indians would become citizens and mission lands would be distributed. The Franciscans had no intention of releasing their charges, whom they viewed as perpetual children in need of supervision. Governors controlled military escorts, approved or blocked new foundations, and held ultimate legal authority. Yet the padres wielded enormous practical power through their control of California's agricultural economy and their status as the only effective administrators of the Indian population. This conflict between civil and religious authority would simmer through the Spanish period until Mexican liberals finally forced secularisation in the 1830s.

The Mission Enterprise

Each mission was a self-sustaining unit run by two Franciscan priests with a small escort of soldiers and their families. It served as an agricultural, craft manufacturing, and Catholic conversion centre. The largest, Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, housed about 3,000 Indians at its peak. In 1829, American trader Alfred Robinson wrote:

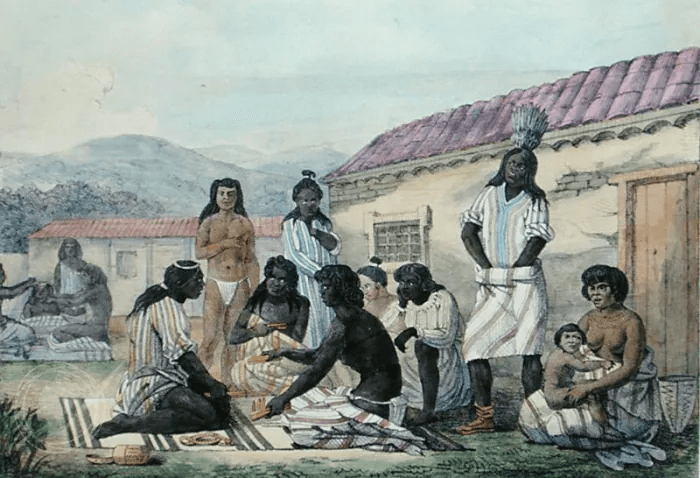

"All were employed in various occupations. Some were engaged in agriculture, while others attended to the management of over sixty thousand head of cattle. Many were carpenters, masons, coopers, saddlers, shoemakers, weavers, etc., while the females were employed in spinning and preparing wool for their looms".2

The missions reached their economic zenith in the early 1820s. They held 200,000 sheep, 150,000 cattle, and 20,000 horses grazing across hundreds of thousands of acres. Mission forges introduced ironworking to California. Workshops turned raw hides into saddles and shoes. Fields produced wheat, barley, and corn. They made soap and candles from tallow, wove blankets from wool, pressed olives into oil, and crushed grapes into wine. The hides of the cattle were shipped to Boston in exchange for manufactured goods. Through the labour of thousands of neophytes, the missions sustained the military and civil government of California.

Mission bells regulated daily life. Neophytes rose at dawn for Mass, worked five to seven hours depending on the season, had a midday meal of beans and corn, then returned to work until evening prayers. Children also worked, scaring birds from gardens, serving at Mass, and hauling water.

The missions transformed California from a land of hunter-gatherers into an agricultural province producing export surpluses. They created a class of skilled Indian craftsmen trained in European techniques. In the 1830s, Pablo Tac, a Luiseño man raised at Mission San Luis Rey, described how the padre ruled his domain "like a king", presiding over "his pages, alcaldes, major domos, musicians, soldiers, gardens, ranchos, livestock, horses by the thousand, cows, bulls by the thousand, oxen, mules, asses, 12,000 lambs, 200 goats".3

Isolation and Visitors

The founding of Los Angeles in 1781 coincided with disaster. That year, the Yuma revolt on the Colorado River severed the overland route from Sonora, isolating California. The sea route from San Blas, with strong southerly currents and headwinds, was unreliable. In good years, two supply ships made the voyage; in several, none came. California was becoming an orphan of the Spanish Empire, a coastal string of missions and three small pueblos: San José (1777), Los Angeles (1781), and Villa de Branciforte (1797), which never thrived and was eventually absorbed into Santa Cruz.

Yet even as California languished in isolation, it attracted foreign visitors. French, British, Russian, and American expeditions charted the coast throughout the 1780s and 90s, their reports documenting California's harbours and resources for distant capitals.

The most substantial foreign presence came from Russia. In 1812, the Russian-American Company established Fort Ross (from Rossiya, Russia), seventy miles north of San Francisco, a permanent settlement with a fortress, Orthodox chapel, workshops, windmills, tannery, and agricultural fields worked by Aleut and Kashaya Pomo labourers. At its peak, Fort Ross housed around 400 people. It represented Russia's southernmost claim in North America, a direct challenge to Spanish and later Mexican sovereignty. The Russians sought furs, not territory, but California's sea otter population was already depleted by the 1820s, and agricultural operations struggled with California's summer-dry climate. In the 1830s, General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo was assigned to establish a Mexican military presence at Sonoma, partly to counterbalance Russian influence. But the Russians proved peaceful neighbours, more interested in farming and trade than territorial expansion. By the late 1830s, the Russian-American Company abandoned the settlement.

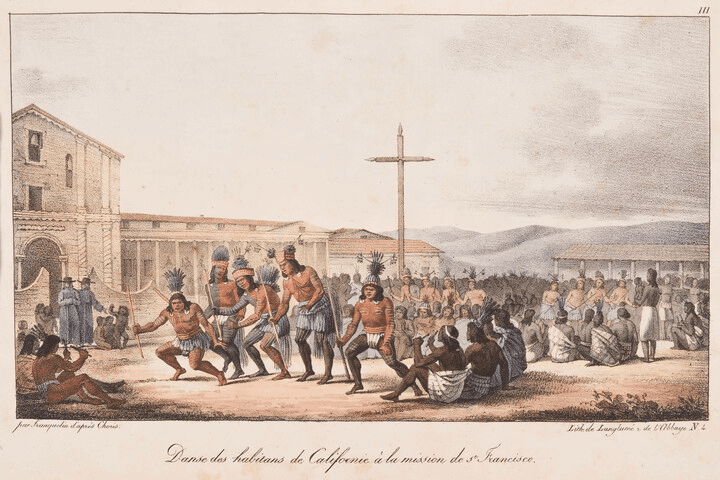

In 1816, a Russian expedition brought the Ukrainian artist Ludwig Choris to California. His watercolours and lithographs became some of the earliest visual records of Native Californians, capturing the Chumash, the Ohlone, and the Pomo with ethnographic precision rare for the era. His images preserved what the missions were destroying: a glimpse of California's indigenous peoples before demographic collapse rendered them nearly invisible to history.

Some visitors never left. That same year, Thomas Doak, a Bostonian who jumped ship at Monterey, converted to Catholicism, married the daughter of prominent citizen Mariano Castro, and within a year was painting the reredos at Mission San Juan Bautista. He was the first of many Americans to reinvent themselves in California. These early deserters and adventurers set a pattern that would accelerate in the decades to come. Foreign contact was no longer limited to diplomatic missions and trading vessels. Individuals were putting down roots, converting, intermarrying, and becoming Californios. The boundary between visitor and settler was dissolving.

The Iron Hand

In 1806, the German physician Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff visited California as part of a Russian-led expedition. He wrote

"two or three monks, and four or five soldiers, keep in order a community of a thousand or fifteen hundred rough uncivilised men, making them lead a wholly different course of life from that to which they had been accustomed, without any spirit of mutiny or insurrection appearing among them".4

Langsdorff appears to have been left with a rosy impression of the missions.

"... the monks conduct themselves in general with so much prudence, kindness, and paternal care, towards their converts, that peace, happiness, and obedience universally prevail among them. Disobedience is commonly punished with corporal correction, and they have only recourse to the military upon very extraordinary occasions; as for instance, when they go out in search of converts, or have any reason to apprehend a sudden attack".5

Such control was only possible through systematic coercion. The Spanish regarded baptism as a definitive and irrevocable choice. Once converted, neophytes were expected to remain at the mission permanently. Leaving without permission was forbidden. At night, the mission gates were locked, and sentries were posted. Visiting a neighbouring village required a written pass from the padre. Soldiers pursued those who fled, dragged them back tied to saddles, and publicly whipped them as an example to others. Still, mission records document hundreds of escape attempts. At Mission San Gabriel alone, there were 473 documented runaways between 1769 and 1817.6

Twenty-five lashes with a rawhide whip was considered a light punishment. More serious infractions like repeated attempts to escape, refusal to work or practising traditional ceremonies could bring fifty or a hundred lashes, weeks in shackles, or confinement in the stocks. At Mission San José in 1826, English Naval Captain Frederick William Beechey observed:

"The congregation was arranged on both sides of the building, separated by a wide aisle passing along the centre, in which were stationed several alguazils with whips, canes, and goads, to preserve silence and maintain order, and, what seemed more difficult than either, to keep the congregation in their kneeling posture. The goads were better adapted to this purpose than the whips, as they would reach a long way and inflict a sharp puncture without making any noise. The end of the church was occupied by a guard of soldiers under arms, with fixed bayonets"7

The system relied partly on indigenous enforcers. The Padres appointed respected neophytes as alcaldes to report misbehaviour and help administer punishment. Some missions organised Indian militia companies, giving trusted natives muskets to guard the compound or pursue fugitives. This created a class of Hispanicised Indians complicit in controlling their own people under Spanish supervision.

The missions also concentrated people from different tribes, many with long histories of enmity. When missions expanded rapidly, they drew Indians from increasingly distant and rival villages, concentrating peoples who had competed for resources for generations into confined quarters where old enmities festered. In 1785, Nicolás José, a baptised Gabrielino who had served as a mission alcalde, organised a rebellion at San Gabriel after the padres banned traditional ceremonies, including the annual Mourning Ceremony for honouring the dead. He enlisted Toypurina, an unbaptised woman from Japchivit village, to rally support. When captured, she testified that she "was angry with the Padres and with all of those of this Mission because we are living here in her land". Her anger, Spanish officials concluded, was directed not only at the missionaries but at the hundreds of recently baptised coastal Gabrielinos who had relocated to the expanding mission, revealing how Spanish colonisation intensified pre-existing rivalries between indigenous groups competing for land and resources.8

Between 1769 and 1834, the Franciscans baptised 53,000 Indians and buried 37,000. At many missions, three of four children died before age two. Crowding thousands of people with no immunity to European diseases into confined quarters created perfect conditions for epidemics. Measles swept through Mission San Francisco de Asís in 1806. Smallpox struck La Purísima in 1834 and San Francisco again in 1838. The mission at Soledad lost most of its neophytes to disease in 1802. The pattern repeated across all twenty-one missions: baptism, conversion, death.

Even Padre Mariano Payeras, president of the missions, grew despondent. In 1820, he warned his superiors that at the current rate, "a few years hence, on seeing Alta California deserted and depopulated of Indians, it will be asked, where is the numerous heathendom that used to populate it?" His answer was bitter: "The missionary priests baptised them, administered the sacraments to them, and buried them".9

The missions were volatile institutions maintained by coercion, even as disease hollowed them out. In 1824, when Chumash Indians at three missions, Santa Inés, La Purísima, and Santa Barbara, revolted simultaneously, the rebellion was suppressed within weeks, but it exposed the fragility of a system that depended on the submission of thousands to the authority of a handful. The missions were not the peaceful, prosperous communities they appeared to visitors like Langsdorff. They were cemeteries built on force.

The missions never achieved their stated purpose. The system aimed to transform Native Americans into Hispanic citizens who would integrate into California's civil society. Instead, Indians remained perpetual children under Franciscan authority. The friars discouraged intermarriage with settlers and refused to release neophytes to work in the pueblos. As historian Kevin Starr noted:

"... a steady stream of Hispanicized Native Americans should long since have been transferring into the civil population of California. This never happened. Either the Indians died off, or they became permanently missionized (which is to say, wards of the Franciscans), or they fled into the interior"10

The Long War and California's Abandonment

In September 1810, as California's missions reached their economic zenith, events in Mexico shattered the colonial order. Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, parish priest of the small town of Dolores in the Bajío region, rang his church bells and issued a call to arms. His Grito de Dolores (Cry of Dolores) launched Mexico's War of Independence, a brutal civil conflict that would consume the viceroyalty for eleven years.

The war had its roots in Napoleon's invasion of Spain in 1808. When French forces imprisoned King Ferdinand VII and installed Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne, the legitimacy of colonial government collapsed. In Mexico, tensions between peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain) and criollos (Spaniards born in the Americas) erupted into violence. Hidalgo's movement called for the end of 300 years of Spanish rule, redistribution of land, and racial equality. The rebellion was chaotic and poorly organised. Hidalgo was captured and executed in 1811. His successor, Father José María Morelos, proved a more effective military leader but was also captured and executed in 1815. A stalemate persisted until 1821, when Mexican conservatives, alarmed by Spanish liberal reforms, allied with the rebels they had been fighting. Agustín de Iturbide negotiated independence, which was granted on 24th August 1821. What had begun as a popular revolution ended as a conservative coup.

California experienced the war as abandonment. By 1810, Spain's treasury was bankrupt, and financing for military payroll and missions ceased entirely. The supply ships from San Blas stopped coming. For more than a decade, California received almost nothing from the mother country.

The distance insulated California from the violence consuming Mexico. No battles were fought in Alta California. The war was simply an absence of supplies, of funding, of attention. To prevent starvation, local authorities relaxed trade restrictions, allowing contact with foreign merchants. English, Russian, and American ships began calling at Californian ports with increasing frequency, trading manufactured goods for hides and tallow. The isolation that had made California a Spanish backwater now opened it to global commerce.

Part 2: Mexican California

News of Mexican independence reached California in 1822, a full year after the Treaty of Córdoba. The Franciscans swore allegiance to the new Mexican Republic, but the change felt more nominal than real. Mexico City sent no new governor until 1824. The missions continued operating as they had under Spanish rule. The soldiers' pay remained in arrears. For more than a decade after 1821, Spanish colonial institutions persisted intact, governed now by Mexican authority in name but functioning exactly as they had under the crown. Contact with foreign traders had created commercial relationships that bypassed Mexico City entirely. The isolation had bred a distinct Californio identity, neither fully Spanish nor fully Mexican.

Yet in Mexico City, liberal reformers were gaining influence. The missions, they argued, were retrograde, royalist institutions: relics of Spanish colonialism incompatible with republican ideals. The Franciscans had been agents of the crown. The mission system concentrated vast wealth and land in a religious order rather than productive citizens. In 1833, the Mexican Congress demanded secularisation.

The Great Land Giveaway

The mission lands were to be distributed first to the Native peoples who worked them, then to soldiers and citizens who served the colony. The intent was to transform mission Indians into landowning citizens of the Mexican Republic. Governor José Maria Figueroa, of Native American descent and regarded as the most competent governor of the Mexican era, fought hard to realise this vision.

When Mexican entrepreneurs José María Híjar and José María Padrés (yes - three José Marias) proposed a colonisation scheme diverting secularised mission lands to 250 settlers, Figueroa opposed them. He argued these were Indian lands, held in trust for them by the Franciscans. President Antonio López de Santa Anna backed Figueroa, cancelling Híjar's commission as governor whilst he was en route. On 4th August 1834, Figueroa issued a 180-page proclamation taking charge of secularisation. Half of all properties would go to mission Indians, and the missions would be secularised in stages: ten in 1834, six in 1835, and five in 1836.

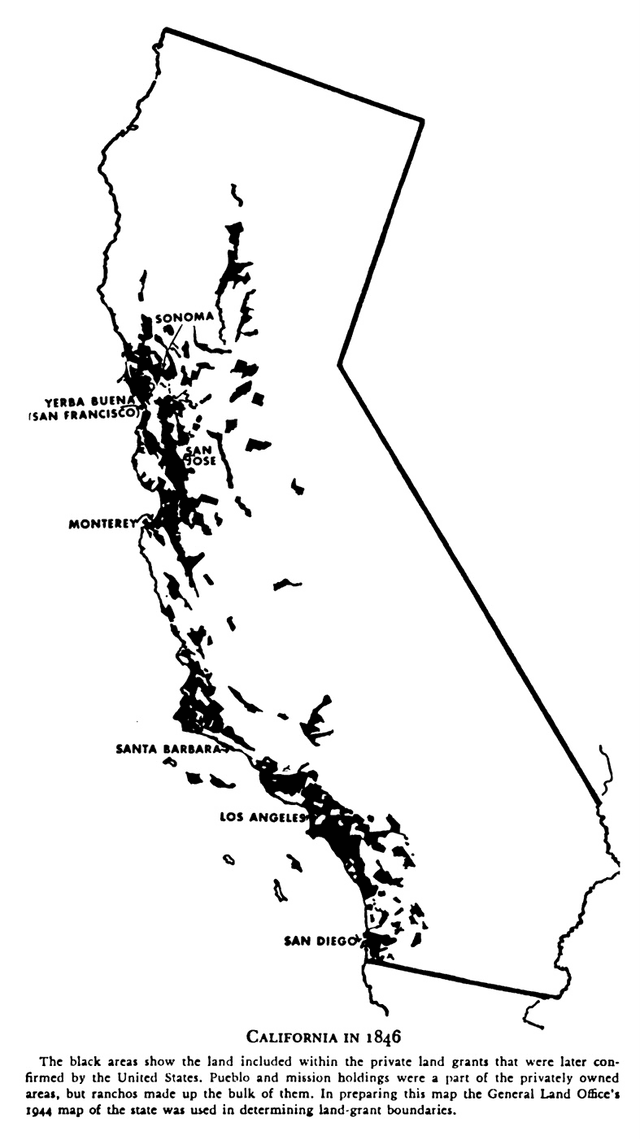

It was a noble plan, but it failed. Twenty thousand Indians were ostensibly freed to become citizens and landowners. In reality, most had nowhere to go. The traditional village economies had been shattered by decades of mission control. The lands they had once inhabited were now parcelled into private estates. Their former mission fields and herds belonged to rancheros. Most Indians who obtained allotments soon sold them for cash or lost them to legal manipulations by their more sophisticated neighbours. The real beneficiaries were the gente de razón (people of reason), a term for non-Indians.

In little more than a decade, the transformation was complete. Mission lands supporting thousands of Indian workers were divided into large private estates. The herds of cattle and sheep that had belonged to the missions now grazed on private ranchos. Thousands of Indians drifted from the ruins of the missions to the new ranchos, seeking subsistence. The ranchos inherited not only the missions' lands and livestock, but also their people.

Indian labour sustained the rancho economy. "Among the Mexicans there is no working class; (the Indians being slaves and doing all the hard work)", Richard Henry Dana observed.11 Larger ranchos maintained rancherías, settlements of Indian workers living in adobe huts near the main hacienda, receiving rations of beef and corn in exchange for their labour. They broke horses, herded cattle, rendered tallow, built adobe walls, tended gardens, and served in the casa.

Legally, Indians in Mexican California were free persons. Slavery was outlawed. In practice, the ranchos operated on peonage and debt servitude. Rancheros advanced goods to Indian workers and paid wages so low that debts accumulated faster than they could be repaid. Workers became bound to the estate, unable to leave. Conditions on many ranchos were brutal. The death rate among Indian rancho workers was roughly double that of enslaved African Americans.12 Disease, overwork, malnutrition, and alcoholism took a horrific toll. Owners often paid in aguardiente ("fire water", distilled alcoholic beverages) rather than goods. Violence and intimidation, carried over from mission days, enforced obedience. Disobedient workers could still face the whip or shackles.

The irony was not lost on everyone. Hugo Reid, a Scottish ranchero who married a Gabrielino woman and ran Rancho Santa Anita with Indian labour, wrote in 1846 that California's Indians had been degraded into a state but little better than slavery. He was describing the system he participated in. Abel Stearns, another foreign-born ranchero who amassed vast holdings in Southern California, relied entirely on Indian workers while enjoying the life of a feudal lord.

The romantic vision of the rancho era, gracious dons and guitar music under the stars, rested on the backs of a people whose demographic collapse had begun in the missions and continued on the ranchos. By the late 1840s, as American emigrants poured into the Sacramento Valley and war loomed on the horizon, California's Native population had been so decimated that rancheros feared a labour shortage.

Days of the Dons

This period would be remembered as the "Days of the Dons." Men like Don José Andrés Sepúlveda became the lords of vast domains. In 1837, Governor Juan Bautista Alvarado granted him his Rancho San Joaquín in present-day Orange County, which sprawled across eighty square miles. At his hacienda Refugio, Don José and his family lived a life of pastoral abundance, romanticised by later generations. There were horse races and rodeos, hospitality and feasts, sustained by Indian labour and vast cattle herds.

Mexican California was remembered as a land of gracious dons and doñas, proud horsemanship and generous hospitality, guitar music and moonlit fandangos. For many Californians looking back from the late nineteenth century, rancho life represented California at its best: a simpler, more humane society before American conquest and the gold rush.

The ranchos were pastoral estates built on a simple premise: cattle in exchange for goods. Vast herds grazed unenclosed across leagues of land, tended by mounted vaqueros who rounded them up periodically for slaughter. The rancheros wanted not meat but hides and tallow - rendered fat boiled in great iron kettles. Dried cowhides, stretched and cured, became "California banknotes", the province's de facto currency. Nearly every transaction was paid in silver or hides.13

This humble commerce plugged California into global trade. Boston firms like Bryant, Sturgis & Company orchestrated a four-way exchange. Manufactured goods were shipped to California. A leg of the voyage went to China with sea otter pelts. Then back to California with Chinese silk and porcelain, before California hides were sent to New England factories to become boots and saddles. At every coastal settlement, hide houses lined the beaches, stacked high with thousands of dried hides awaiting pickup by Yankee trading vessels. Sailors at San Diego hurled hides over coastal bluffs to longboats below, backbreaking labour that sustained California's export economy.

Before 1834, only thirty ranchos existed in Alta California. Between 1835 and 1846, hundreds of land grants were issued. In little more than a decade, eight million acres - coastal plains, interior valleys, entire mountain ranges - passed into private hands. A typical rancho grant measured four to eleven leagues, anywhere from 4,000 to 50,000 acres. These were virtually fiefdoms, and their owners styled themselves as landed gentry, adopting the title don and hosting fandangos that lasted days.

When secularisation scattered the mission herds into private hands, the animals multiplied prodigiously on California's grasslands. Beef was so abundant that it was almost worthless; slaughtered cattle were stripped of their hides and left to rot. What mattered was the steady flow of hides to Boston and tallow to soap factories, paid for with imported luxuries the ranchos could not produce themselves: fine cloth, furniture, wine, and metal tools.

Rancheros operated on credit, borrowing against future hide deliveries. When the Panic of 1837 disrupted global commerce, Boston traders scaled back operations. Californios found themselves with surplus hides and no buyers, flush with cattle but desperately short of cash. By the 1840s, many ranchos carried substantial debts to the foreign merchants who controlled coastal trade. The province imported more than it exported. The pastoral abundance masked a precarious dependence on forces beyond California's control.

The Overland Infiltration

By the 1820s, foreigners were arriving in California by two routes: maritime traders sailing via Cape Horn, and overland emigrants crossing the deserts and mountains from the east.

Jedediah Smith led the first American party overland in 1826, crossing the desert and Sierra Nevada to Mission San Gabriel. Mexican authorities ordered him to leave. When he tried to return in 1827, his party was massacred by Umpqua Indians in the Oregon Territory. Smith had proved California could be reached overland, but at terrible cost. Others followed more successfully. Mountain men like William Wolfskill and George Yount arrived in the early 1830s, converted to Catholicism, received land grants, and transformed themselves into gentleman rancheros, cultivating vineyards and establishing estates in Los Angeles and the Napa Valley.

Maritime traders discovered that success in California required becoming Californios. Most converted to Catholicism, learned Spanish, and married into prominent families. American traders like Alfred Robinson and Abel Stearns wed daughters of distinguished Californio families and became rancheros themselves, naturalised Mexican citizens indistinguishable from the Californios except by birth. English and Scottish merchants like William Petty Hartnell filtered up from South American Pacific ports, bringing commercial connections and Old World education.

Thomas Oliver Larkin was different. Arriving in Monterey in 1832 with his wife, Rachel Holmes, the first American woman to live in the province, they remained Protestant and American. Larkin established himself as the most prominent American merchant. When the United States appointed him consul in 1844, he also became a confidential agent with secret instructions to encourage Californios toward independence from Mexico and alignment with the United States.

In 1839, John Augustus Sutter arrived, fleeing debts in Europe via Hawaii and Alaska. Governor Alvarado granted him 48,000 acres in the Sacramento Valley, where Sutter built Nueva Helvetia (New Switzerland), a European-style fort that became part trading post, part agricultural estate, part military installation. He was ruthless with California's Indians, using them as forced labour, but generous to arriving Americans. Nueva Helvetia became the destination for exhausted emigrants stumbling down from the Sierra, offering rest, provisions, and employment. Before Sutter, overland travellers had no reliable refuge in California's interior. After 1839, they had a destination.

The great wave began in 1841. That November, two parties arrived almost simultaneously: the Bartleson-Bidwell party struggled over the Sierra Nevada, half-starved and having abandoned their wagons, whilst the Workman-Rowland party took the southern route via the old Spanish Trail to Los Angeles. In 1843 and 1844, more organised parties followed, bringing families, livestock, and plans for permanent settlement. The Stevens-Murphy party of 1844 pioneered what would become the primary emigrant trail, though they were forced to winter on the shores of Truckee Lake. They survived. In the winter of 1846–47, the Donner Party camped near that same lake and endured starvation, murder, and cannibalism before survivors were rescued in April. The story became the darkest legend of westward migration, but it did not stem the tide.

By 1846, hundreds of Americans had settled in California, mostly in the Sacramento Valley and around San Francisco Bay. They intermarried with Californio families in coastal towns, controlled much of the region's trade, and had a consul in Monterey secretly working to bring California into the United States. The Californios, despite periodic prohibitions from Mexico City, had welcomed these settlers for the trade and skills they brought. A handful of prominent Californios, frustrated with Mexican neglect, discussed the possibility of American protection with Thomas Larkin. California was increasingly Mexican in name only.

The Birth of San Francisco

Whilst the ranchos flourished in the south and American settlers poured into the Sacramento Valley, a new settlement was taking shape on the peninsula that would transform California more profoundly than any mission or rancho ever could.

San Francisco Bay was magnificent - the finest natural harbour on the Pacific coast, capable of sheltering entire fleets. Yet for sixty years after its discovery, the Spanish and Mexicans had done almost nothing with it. The presidio sat on windswept bluffs, undermanned and crumbling. Mission Dolores huddled inland, perpetually shrouded in fog. But the bay itself, with protected coves and deep anchorages, remained largely unused.

That began to change in 1834, when hide and tallow traders started using a small cove on the bay's eastern shore. The anchorage took its name from the aromatic herb growing wild across the peninsula: yerba buena. In 1835, William Richardson, an Englishman who had jumped ship, converted to Catholicism, and married the presidio commandant's daughter, established a trading post at Yerba Buena Cove. In 1837, he built the first permanent structure: a simple redwood house facing the cove. Others followed. Jacob Leese built a store, and in 1839, Swiss surveyor Jean-Jacques Vioget laid out a street grid, creating the bones of a town from scattered buildings on empty dunes.

By the early 1840s, Yerba Buena had become California's principal anchorage for foreign vessels. Hide houses lined the beach. A handful of American, English, and German merchants operated stores. The settlement remained tiny - perhaps a dozen buildings, fewer than fifty residents - but its character was distinct from the Californio towns to the south. Yerba Buena was a maritime trading post, oriented toward the Pacific and global economy, populated by foreigners who had come for trade rather than land.

In January 1847, after the American conquest, Lieutenant Washington Allon Bartlett renamed the settlement San Francisco, linking the obscure trading post to the venerable Spanish name. Within a year, gold would be discovered, and San Francisco would explode from a village of dozens into a city of tens of thousands, the gateway to the Gold Rush and California's greatest metropolis.

California in Foreign Eyes

Throughout these decades, as foreign vessels called at Monterey and San Francisco, as their captains filed reports, as their passengers published memoirs, a shared international perception developed: California was a paradise squandered by a people incapable of developing it.

In 1841, Eugène Duflot de Mofras, attaché to the French legation in Mexico, completed a confidential survey of California's ports, resources, and defences for his government. His two-volume report recommended French seizure of the province, arguing that Mexican governance was so feeble and the population so sparse that a modest expedition could succeed. "The Californians", he wrote with disdain, "pass their lives on horseback, and their greatest enjoyment is to display their skill in catching cattle with the lasso". He argued "...California will belong to whatever nation chooses to send there a man-of-war and two hundred men".14

The British shared this assessment. In the 1820s and 1830s, the Hudson's Bay Company sent trapping brigades south from its Columbia River headquarters, penetrating California's unmapped interior. Peter Skene Ogden and Alexander McLeod led expeditions that ranged through the Sacramento Valley, mapping terrain no Mexican official had ever visited. The Mexican presence consisted of a string of coastal missions and presidios; beyond the coastal range lay a vast interior that Mexico claimed but did not control. In 1841, Sir George Simpson, Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company's vast North American territories, visited California personally. Simpson's journals drip with contempt for California's pastoral somnolence. He described a country of "Nature doing everything and man doing nothing", vast resources squandered by a people lacking the industry to exploit them.15 His verdict was clear: California was ungoverned and ungovernable under Mexican rule. In the end, Britain decided against colonial adventures in California, partly because the Oregon Territory dispute with the United States demanded diplomatic caution, but Simpson's dismissive assessment added to the chorus of foreign voices arguing that Mexican California was a prize waiting to be claimed.

Richard Henry Dana, sailing the coast in 1835, observed, "In the hands of an enterprising people, what a country this might be!"16 The charge of indolence became a refrain in travel accounts. Californios rose late, took long midday siestas, spent evenings in fandangos and horsemanship displays rather than improving their estates. Foreign visitors struggled to make sense of California's pastoral abundance without the visible industry they associated with prosperity. But what looked like idleness to industrious Yankees was simply a different economic logic. California's climate and geography - reliable rainfall, perennial grasses, temperate winters - made pastoral ranching extraordinarily productive without intensive labour. The land supported vast herds with minimal intervention. Why strain after improvement when the earth yielded so generously? The question never occurred to visitors schooled in New England's rocky soil and harsh winters, where survival demanded relentless toil.

More fundamentally, foreign critics observed a hierarchical society and mistook aristocratic leisure for universal indolence. They saw dons at leisure but ignored the vaqueros riding rangeland at dawn, the Indian labourers rendering tallow in great kettles, the artisans working forges and looms. The rancho economy functioned, produced, and traded globally. But it did so without matching Anglo-American notions of visible industry and capital accumulation. The critique revealed more about the critics than California.

Yet these judgements had consequences. The "lazy Californio" became a stock figure in American discourse about the West, serving the same ideological function as the "savage Indian" who wasn't "using" the land. If Californios were squandering a paradise through indolence, then a more enterprising people would rescue it. The diagnosis was universal and convenient: the Californios were pleasant enough people, generous hosts, magnificent horsemen, but fundamentally incapable of exploiting the paradise they inhabited. Whether the solution was French seizure, British colonisation, Irish settlement, or American annexation varied by the observer's flag. But the diagnosis was identical: California was a prize waiting to be claimed.

Gathering Storm

California was slipping from Mexican control. In 1836, Juan Bautista Alvarado led a coup against the Mexican-appointed governor, declaring autonomy. Four years later, the fragility of his regime became clear when he turned on the very American riflemen who had helped him seize power. Alvarado arrested Isaac Graham, a Kentucky frontiersman who had established California's first distillery, along with forty-six other foreign residents, shipping them in chains to Mexico for trial. The Graham Affair provoked British and American diplomatic protests and forced their release, but it exposed the paradox of Mexican California: the regime could not control the foreigners it had welcomed, nor could it expel them without drawing international attention.

As the 1840s progressed, the question was no longer whether California would change hands but when, how, and to whom. The Californios themselves were deeply divided. Most resented the foreign condescension and remained loyal to Mexico, however frustrated they were with the distant government's neglect. But a small group of prominent northern Californios, led by General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, had concluded that Mexican rule offered neither security nor prosperity. They believed American annexation might be preferable to the chaos of continued Mexican governance, though few welcomed the prospect of conquest.

In 1845, another governor was overthrown by combined Californio forces under Pío Pico and José Castro. These episodes of civil strife disrupted the economy and created legal uncertainty. North fought South. Land titles remained provisional, dependent on confirmation from distant Mexico City. There was no robust legal framework, no courts to settle disputes. Local alcaldes handled petty matters, but serious conflicts were settled by force.

Indian raids from the interior increased as ex-mission Indians and autonomous tribes challenged the rancho encroachment. The Californios tried to extend their authority northward, establishing a military district beyond San Francisco Bay under the command of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo. In the 1830s, he had been tasked with secularising Mission San Francisco Solano and founding the pueblo of Sonoma as the northernmost outpost of Mexican California. He had built a casa grande, established vineyards, distributed land to loyal soldiers, and created a miniature fiefdom in the Sonoma Valley.

But Vallejo commanded only a handful of soldiers, most unpaid for months. The Russians at Fort Ross were peaceful neighbours, more interested in farming than conquest, and they would sell out in 1841 anyway. The real threat came from the east: American settlers flooding into the Sacramento Valley, beyond Mexican authority, answering to no one. Vallejo recognised this. He cultivated friendships with American settlers, welcomed them to Sonoma, and discussed openly the benefits of American annexation. It was a pragmatic calculation: Mexico had abandoned California; perhaps the Americans would develop it. This put Vallejo at odds with most Californios, who remained suspicious of American intentions despite their own frustrations with Mexico City. The rancho era was already dying when John C. Frémont rode south from Oregon in spring 1846, trailing a bodyguard of Delaware Indians and nursing dreams of conquest.

Part 3: The American Conquest

The 33-year-old Army captain was a man of contradictions: French-descended, born out of wedlock, he had overcome illegitimacy through charm, audacity, and marriage to Jessie Benton, daughter of Senator Thomas Hart Benton, the "high priest of Manifest Destiny". Jessie transformed Frémont's expedition notes into the Report of the Exploring Expedition to Oregon and North California, published in 1845 to enormous acclaim, casting her husband as the "Pathfinder". Where Frémont was reckless and impulsive, Jessie was strategic and disciplined. Together, they formed a formidable partnership, with Frémont as the public face and Jessie as the hidden architect of his reputation.

By early 1846, Frémont was leading his third expedition into the Far West: 60 men, heavily armed, with the legendary Kit Carson as chief of scouts. Ostensibly a scientific and cartographic mission, the expedition's military character was unmistakable. The United States and Mexico were edging towards war over Texas. California, nominally Mexican but barely governed, hung like ripe fruit waiting to be plucked. And Frémont, nursing dreams of becoming Governor, perhaps even President, intended to be the man who plucked it.

Provocations at Gavilán Peak

In January 1846, Frémont approached Monterey with his armed force. California's government was divided and weak: Governor Pío Pico ruled from Los Angeles, whilst José Castro served as comandante in Monterey. The capital had been moved south due to bitter north-south rivalries, leaving Castro with military authority but no civil power.

Larkin had been quietly cultivating relationships with prominent Californios, encouraging them to consider independence from Mexico and alignment with the United States. His approach was diplomatic, patient, and designed to bring California into the American orbit through persuasion rather than force. Frémont's arrival threatened to upset this delicate work.

After initially camping at Sutter's Fort, Frémont moved toward Monterey. Comandante Castro ordered him out of California. A prudent officer would have complied or at least withdrawn quietly. Frémont did the opposite. He took his men to Gavilán Peak overlooking Monterey, erected rough log fortifications, and on 6th March, raised the American flag. For three days, the Stars and Stripes flew defiantly over Mexican territory whilst Castro assembled a militia below. It was a calculated provocation, signalling American intentions six months before their navy would arrive.

Then, inexplicably, on the night of 9th March, Frémont struck camp and moved north toward Oregon. He claimed later that the flagpole had blown down, a convenient explanation for what looked like a strategic retreat. Whatever the reason, the American flag came down, and Frémont disappeared into the northern wilderness.

The Gillespie Mission

In April, Marine Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie arrived in California disguised as a travelling merchant. The American Navy ship Cyane had ferried him from Hawaii. He carried confidential dispatches from President James Polk and Secretary of State James Buchanan for Larkin. After delivering them, Gillespie pursued Frémont into Oregon, catching up with him at Klamath Lake on 8th May.

What Gillespie told Frémont remains one of the great controversies of California history. Frémont claimed he received confidential orders to seize California. Most scholars dispute this, believing that Gillespie carried only routine dispatches and perhaps verbal encouragement but nothing so explicit as orders for conquest. The truth is unknowable. Gillespie destroyed his papers. Frémont's memoirs are self-serving. What matters is what happened next. On 13th May, the United States declared war on Mexico. But this news would not reach California for months. In the meantime, Frémont would act as if he had received orders that may never have been given.

The Bear Flag

Frémont returned from Oregon in late May, riding in Napoleonic splendour with his Delaware bodyguard. His reappearance electrified the American settlers around Sonoma. On 14th June, a group of frontiersmen and adventurers seized Vallejo, the same commander whose open sympathies for American annexation made him an unlikely target, at his Sonoma rancho. Vallejo was imprisoned whilst the insurgents liberated his wine cellar.

The rebels declared the California Republic and created a flag: a red star, a grizzly bear, and the words "California Republic" on a white field. The bear was crudely drawn, prompting one observer to suggest it resembled a pig more than a bear. No matter. The Bear Flag flew over Sonoma as a symbol of American defiance.

Frémont quickly assumed personal control of the Bear Flaggers, who pledged allegiance to the United States rather than their brief republic. He dashed to the mouth of San Francisco Bay and spiked the ancient Spanish cannons guarding the harbour. In his report the previous year, Frémont had coined a name for the bay's mouth, inspired by the Golden Horn of Constantinople: Chrysopylae, or the Golden Gate. The gesture was theatrical but effective. California was being seized, mission by mission, presidio by presidio, not by official American forces but by irregulars operating under the protection of an Army captain who may or may not have had orders.

The Navy Arrives

On 7th July, Commodore John Drake Sloat, aged and ailing, finally raised the American flag at Monterey. The 65-year-old had been waiting offshore for weeks, paralysed by caution, unsure whether to act without official notice of war. But hearing rumours of the Bear Flag revolt and hostilities in Texas, and fearing his hesitation would cost him his command, Sloat reluctantly decided to seize California. On 12th July, the Stars and Stripes rose over San Francisco. The American conquest had become official, but Sloat remained anxious that he had overstepped his authority.

On 23rd July, Commodore Robert Field Stockton, handsome, wealthy, socially connected, and ambitious, relieved Sloat of command. Stockton was everything Sloat was not: aggressive, confident, eager for glory. He immediately authorised Frémont as brevet major of the newly established California Battalion of Mounted Riflemen. The battalion was an eclectic force: Frémont's original expedition members, mountain men, Delaware Indians, Bear Flaggers, with Gillespie promoted to brevet captain as second in command and Kit Carson remaining chief of scouts.

Blood on the Trail

The California Battalion left a trail of violence as it moved south. In the Sacramento Valley, they slaughtered a Maidu Indian village, killing men, women, and children. The massacre served no military purpose; it was terror.

Near San Rafael, three Californios rowing across the bay were spotted by Frémont's scouts. Francisco de Haro's twin sons, nineteen years old, and their uncle José Berryessa, were unarmed civilians. Kit Carson and his men shot them in cold blood as they came ashore. When the old man begged for his life, Carson killed him anyway. These were not combat deaths but executions, designed to terrorise and intimidate.

The killings violated every code of warfare and dishonoured the American cause. They were also effective. Word spread through California: the Americans were ruthless, and resistance would be met with murder.

Naval ships transported the battalion from Monterey to San Diego, where they were re-horsed and re-provisioned. Los Angeles, the largest settlement in Alta California, fell under American rule on 13th August. Governor Pío Pico fled toward Mexico. Captain Gillespie was left in charge of the pueblo, and Stockton prematurely declared California conquered.

The Californio Rising

Gillespie's administration of Los Angeles was harsh and insulting. He imposed a curfew, banned gatherings of more than three persons, and treated the Californios as a conquered people, which, technically, they were, but the manner mattered. Within weeks, an insurrection erupted. José María Flores, a Mexican army captain, rallied the Californios. Gillespie was forced to flee Los Angeles, retreating to San Pedro, where he awaited relief.

A detachment of Marines attempted to retake the pueblo and failed. The Californios, dismissed by many Americans as indolent and unwarlike, proved formidable when defending their homeland. They were superb horsemen, skilled with the lasso and lance, and they fought with the advantage of local knowledge.

The most significant engagement came on 6th December, at San Pasqual, a village northeast of San Diego. Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny's Army of the West, 121 dragoons who had marched overland from New Mexico, encountered a Californio force under Andrés Pico, the governor's brother. The Californios used a classic ruse: they pretended to flee. The American dragoons broke formation in pursuit, charging pell-mell after the retreating enemy. Then the Californios wheeled and counterattacked.

The battle that followed was brutal and personal. The Californios wielded twenty-foot willow lances with devastating effect in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Twenty-three American dragoons died, including several officers. Kearny himself was wounded twice. It was the bloodiest engagement of the California campaign and a humiliating defeat for American forces. For a brief moment, it seemed the Californios might actually win.

They could not. By January 1847, an overwhelming American force had been assembled: Kearny's dragoons (reinforced and recovered), marines, sailors acting as infantry, Frémont's mounted battalion, and horse-drawn artillery. On 10th January, at the Battle of La Mesa outside Los Angeles, this combined force retook the pueblo. The Californios fought bravely but were outnumbered and outgunned.

Three days later, on 13th January, the Californios surrendered to Frémont under an oak tree in the hills outside Los Angeles. The Capitulation of Cahuenga was generous: Californios could keep their weapons and horses, and there would be no reprisals. The Californios surrendered to Frémont because they believed him to be the most sympathetic of the American commanders. Stockton would have imposed harsher conditions. Kearny, still angry about San Pasqual, might have demanded humiliation.

The treaty ended armed resistance. California was American.

The Governorship Dispute

Victory brought an unseemly squabble. Both Frémont and General Kearny believed themselves to be the legitimate governor of California. Frémont claimed appointment by Stockton; Kearny cited his superior rank and dispatches from Washington. For weeks, California had two men claiming executive authority, each issuing orders and expecting obedience.

Kearny bided his time until Army Colonel Richard Mason arrived as the clearly designated military governor. Then he struck. Frémont was arrested on charges of mutiny and disobedience and ordered to Washington under guard. A court-martial found him guilty on all counts. President Polk, perhaps mindful of Senator Benton's influence, granted Frémont a full pardon.

Frémont resigned from the Army in disgust. He and Jessie wrote another memoir, mounted a private expedition to find a railroad route across the Rockies, and then returned to California for mining and politics. He had conquered California, but California had not made him governor. That honour, such as it was, belonged to military administrators who would govern until statehood came in 1850.

The Treaty

On 2nd February 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally ended the Mexican-American War. Mexico ceded California, New Mexico, and the disputed Texas territories to the United States for $15 million. The United States now stretched from sea to shining sea. Manifest Destiny, the belief that American expansion across the continent was inevitable and divinely ordained, had been fulfilled.

For California, the timing was extraordinary. Nine days before the treaty was signed, James Marshall discovered gold at Sutter's Mill on the American River. The Gold Rush would begin within months, transforming California from a sleepy backwater of 15,000 non-Native inhabitants into a destination for migrants from around the world. By 1850, California's population would exceed 100,000, and statehood would follow.

The conquest of California was less a military achievement than a fait accompli. Mexico's hold on the territory had been weak, divided, and neglected. The Californios themselves were ambivalent about Mexican rule, with some openly favouring American annexation. What Frémont, Stockton, and Kearny accomplished was less conquest than acceleration, rushing forward an outcome that, given the tide of American settlement and the weakness of Mexican authority, might have occurred peacefully within a few years. Instead, it came through violence, deception, and the theatrical ambitions of a man who claimed orders he may never have received. The Bear Flag would become California's official flag in 1911, a symbol of independence and defiance. But its origins lay in an irregular seizure orchestrated by irregular men.

Footnotes

-

https://www.domingosenise.com/book-summaries/history/felipe-de-neve-first-governor-of-california-and-founder-of-the-city-of-los-angeles.html ↩

-

https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=hornbeck_usa_3_d ↩

-

https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?psid=531&smtID=3 ↩

-

https://www.habitatauthority.org/fc/studies/native_american_history.pdf ↩

-

https://ia601300.us.archive.org/31/items/narrativeofvoyag02beec/narrativeofvoyag02beec_djvu.txt ↩

-

https://stevenhackel.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/sources-of-rebellion_-indian-testimony-and-the-mission-san-gabriel-uprising-of-1785.pdf ↩

-

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Cross-Thorns-Enslavement-California%C2%92s-Missions/dp/1610353048 ↩

-

https://www.amazon.co.uk/California-History-Modern-Library-Kevin/dp/081297753X ↩

-

https://chatgpt.com/share/68f4063f-70f0-8005-94cd-e72e721a7092 ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_California_before_1900 ↩

-

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Americans-California-Dream-1850-1915-Kevin/dp/0195042336 ↩

Tags: History